In my last column I provided a warning from history about leaders who assume high office—with all its powers, and perquisites—only to offer platitudes in return. This is a very real and very serious issue because there is a causal link between lack of strategy and the challenges people face in their daily lives. In the political realm this can involve a failing economy, civil unrest, and war.

In organisations the fallout is a microcosm of these broader macro trends, and it is highly corrosive to culture when leaders offer platitudes, burnish their laurels, then demand staff "prove their value to the project". To move beyond this miasma, organisations must adopt a rigorous approach to strategy formulation and implementation which involves four key practices.

1. Deep Analysis: The Foundation of Good Strategy

Effective strategy begins with a nuanced diagnosis of the situation. This diagnosis involves a thorough understanding of both the external environment and the internal capabilities of the organisation. It is not enough to simply state that the company will "innovate" or "expand"; leaders must identify the specific challenges and opportunities that exist within their industry and their organisation, and be able to express what good innovation or good expansion looks like.

This approach is reminiscent of Sun Tzu's principles in The Art of War, where the understanding of the terrain, the enemy, and one's own forces is essential for victory. In the modern business context, this means a detailed analysis of market conditions, customer needs, and the competitive landscape, as well as an honest assessment of the organisation's strengths and weaknesses.

Without this deep analysis, any strategy is likely to be built on shaky foundations. As Rumelt points out, good strategy requires identifying the "kernel" of the problem and crafting a response that addresses it directly.

2. Clear Choices: The Heart of Strategic Success

One of the key elements that differentiate a true strategy from a platitude is the ability to make clear, definitive choices. Given strategy is about making trade-offs, organisations must decide what not to pursue, focusing their efforts on areas where they have a competitive advantage or where they can develop one. As Michael Porter famously articulated:

The Essence of Strategy is Choosing what not to Do.

This knowledge is seldom the result of blue sky thinking on a strategy day, it is the outcome of deep analysis and broad reading of available literature. To be actionable, this knowledge must go far beyond mere 'data', and constitute what Charlie Munger called a 'latticework of models':

The first rule is that you can't really know anything if you just remember isolated facts and try and bang 'em back. If the facts don't hang together on a latticework of theory, you don't have them in a usable form..

Munger (2024)

This is why many 'strategies' falter because to please all stakeholders or avoid difficult decisions, leaders end up articulating broad, non-committal goals that fail to provide real direction. A true strategy requires leaders to make hard choices about where to compete, how to compete, and what to sacrifice to win.

3. Alignment and Execution: Turning Strategy into Action

Henry Mintzberg in The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning notes that many strategies fail not because they are poorly conceived but because they are poorly executed. For a strategy to be effective, it must be aligned across the entire organisation, with every department and team understanding how their work contributes to the overall goals.

This alignment requires clear communication, robust management processes—as opposed to leadership, see Leader-Managers for the difference—and a commitment from leadership to see the strategy through. It also means ensuring that the organisation has the resources—financial and human—to pursue the strategy effectively.

Donald Hambrick and James Fredrickson provide a useful framework for evaluating the quality of a strategy. They suggest that a good strategy should be tested against six key criteria:

- Does your strategy fit with what's going on in the environment? Is there healthy profit potential where you're headed? Does your strategy align with the key success factors of your chosen environment?

- Does your strategy exploit your key resources? With your particular mix of resources, does this strategy give you a good head start on competitors? Can you pursue this strategy more economically than competitors?

- Will your envisioned differentiators be sustainable? Will competitors have difficulty matching you? If not, does your strategy explicitly include a ceaseless regimen of innovation and opportunity creation?

- Are the elements of your strategy internally consistent? Have you made choices of arenas, vehicles, differentiators, and staging, and economic logic? Do they all fit and mutually reinforce each other?

- Do you have enough resources to pursue this strategy? Do you have the money, managerial time and talent, and other capabilities to do all you envision? Are you sure you're not spreading your resources too thinly, only to be left with a collection of feeble positions?

- Is your strategy implementable? Will your key constituencies allow you to pursue this strategy? Can your organisation make it through the transition? Are you and your management team able and willing to lead the required changes?.Hambrick & Fredrickson (2001)

These questions help ensure that the strategy is not just a collection of good ideas but a cohesive plan that can be executed effectively.

4. Continuous Learning and Adaptation: The Role of a Learning Organisation

Given the speed with which technology is evolving the business landscape, a static strategy is a recipe for failure. As Peter Senge argued in The Fifth Discipline, successful organisations are those that can learn and adapt. This means regularly reviewing and updating strategies in response to new information, shifting market conditions, and evolving customer needs.

A learning organisation does not see strategy as a one-time event but as an ongoing process. This approach requires a culture of continuous improvement and open knowledge sharing, where feedback loops are built into the strategic planning process, and leaders are willing to pivot or adjust course when necessary.

Case Study: Ikea

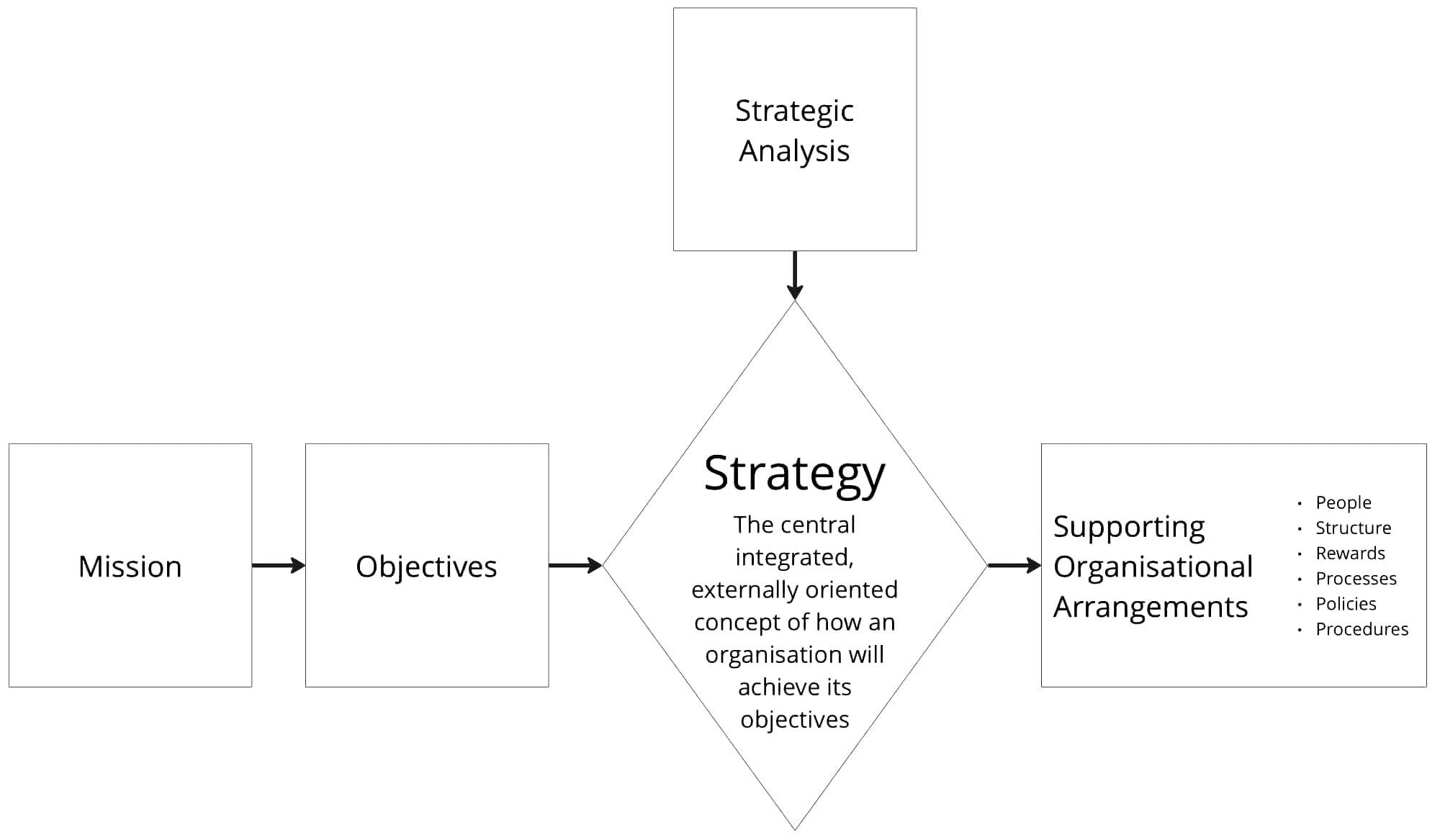

Good strategists understand that a strategy isn't a catchall, rather it is an integrated set of choices that exist in a broader ecosystem. This situates an organisational strategy not as a beacon for people to look toward, but as 'the central integrated, externally oriented concept of how an organisation will achieve its objectives'.

What this model means is that if a newspaper's mission was to be the country's paper of record might, it can be used to guide its strategy, but it is not the entirety of their strategy. Rather, the five elements depicted in Figure 1 beg five questions which need answering before a leader can say "we have a strategy":

- Areas: where will the organisation be active?

- Vehicles: how will the organisation get there?

- Differentiators: how will the organisation win market share?

- Staging: what will be the speed of strategic rollout and the sequence of moves to achieve strategic success?

- Economic Logic: how will returns on investment be achieved?

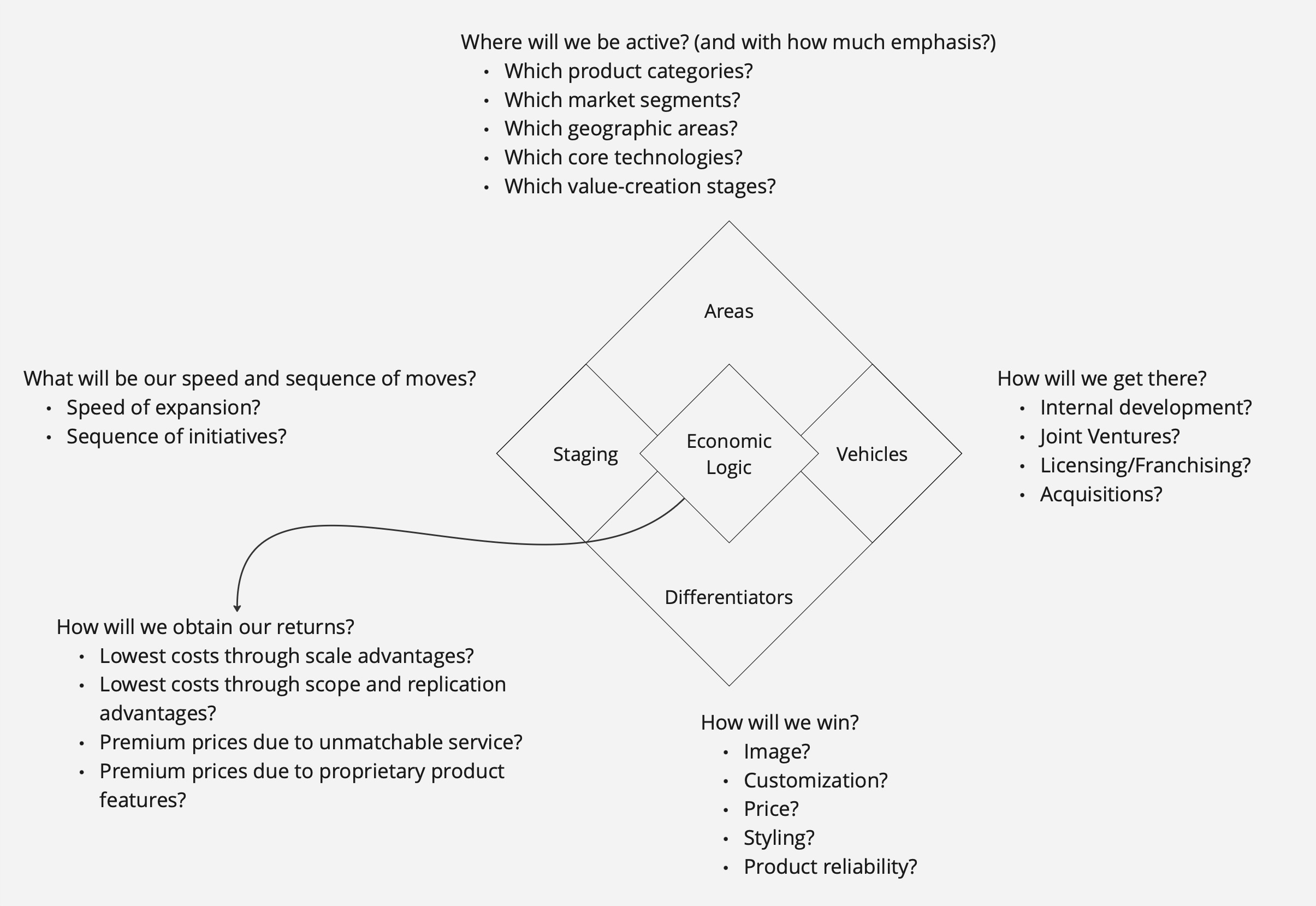

Visualised, these questions look something like this (Figure 2):

The challenge in creating a good strategy is it isn't as simple as coming up with plausible answers to the five questions listed above. Rather, it is about understanding each question is part of a larger, mutually reinforcing set of choices.

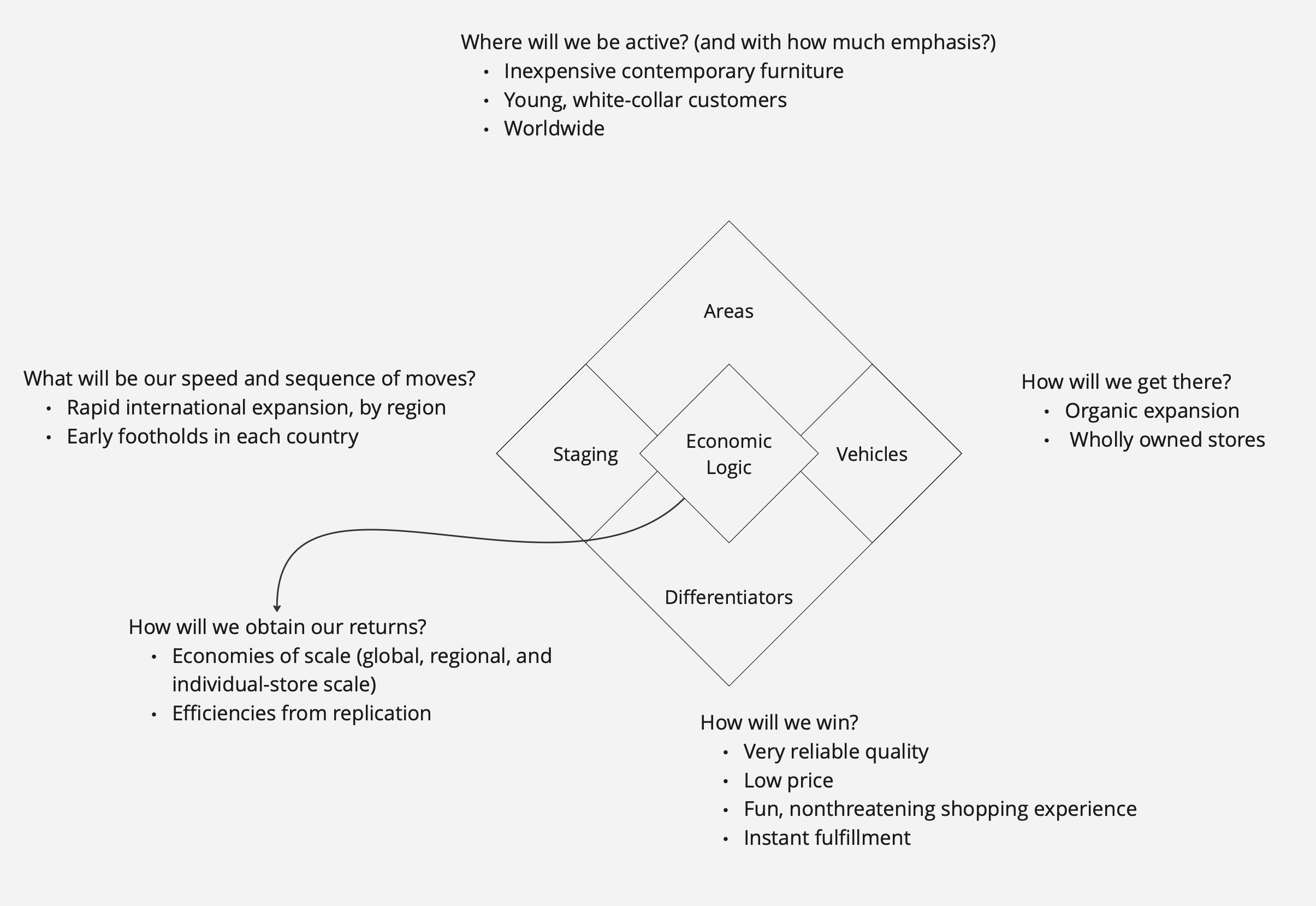

This symbiotic relationship was encapsulated in IKEA's strategy (Figure 3) in which the five elements were mutually reinforcing and led to many years of double digit growth, annual revenue of €44.6 billion, and the global brand we know today.

The Path to Real Strategic Value

To avoid the trap of platitudes, organisations must adopt a disciplined approach to strategy. This involves conducting deep analysis, making clear and sometimes difficult choices, ensuring alignment across the organisation, and committing to continuous learning and adaptation.

As the business environment becomes increasingly complex and competitive, the ability to distinguish between real strategies and platitudes will be a key determinant of organisational success. A well-crafted strategy is not just a beacon for people to look toward, but 'the central integrated, externally oriented concept of how an organisation will achieve its objectives'.

By focusing on specificity, actionability, measurability, coherence, and adaptability, leaders can craft strategies that truly guide their organisations to success. This process situates an organisational strategy not as a collection of platitudes but as a dynamic, living framework that drives real value in an ever-changing world.

Moving beyond platitudes is not just a strategic imperative but a necessity for survival in today's business landscape. Organisations that fail to develop true strategies, grounded in rigorous analysis and clear choices, risk drifting aimlessly in a sea of vague goals and unfulfilled potential. By adopting the practices outlined above, leaders can ensure that their strategies are more than just words on a page—they become the driving force behind sustained competitive advantage and organisational success.

Good night, and good luck.

A Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery by Joseph Wright of Derby (1734–1797) is licensed under Public Domain.