If your working day is anything like mine, it is plagued with busyness. From meetings which should have been emails to emails which should have been a Teams message to Teams messages which should not have been sent — EVERYONE is engulfed by activities which feel to be demanding of immediate attention.

For all this output, most people I speak with finish their working day with the sentiment "I don't know what I got done today", which is usually followed by a look at the to do list and a realisation almost nothing on it got done that day — queue sense of exhaustion at the Sisyphean task that is work. Too much work and not enough time, yet always enough time to be busy. This is the busyness paradox.

If we are busy but not productive it begs the question: how much of what we do in our working day is beneficial and essential? If alarmingly little, what can we do to fix this untenable state of affairs?

The Busyness Paradox

John Maynard Keynes, in his seminal work The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, observed that "Worldly wisdom teaches that it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally." This sentiment underscores our reluctance to deviate from the norm, even if it means engaging in unproductive activities. The result is a workplace culture where busyness is often mistaken for productivity.

Unfortunately, many people who are fashionably called 'knowledge workers' are in fact becoming 'interaction workers'. That is, their day is not spent producing a unit of work — however that is measured — but in interacting with colleagues and systems.

Data is compounding rather than improving the situation. While I am a strong advocate of a SMART goal, there are some things which are difficult if not impossible to measure. Joy from watching a sunset, mirth from hearing a great joke, relaxation from knowing a job was well done. All these things unburden the mind and dramatically improve both our quality of life and, in a business context, the capacity and quality of our work. Taking myself as a case study, when under a lot of pressure and mental strain, writing this column is the heigh of tedium. But when my spirits are high and I have a song in my heart, it is a pleasure to write, and my writing is all the better.

Yet because data has become the default request in all aspects of work, employees in fear of losing their jobs will simply double down on measurable busyness. Calendars will become blocked beyond endurance, meeting contributions will become ever shriller, and as people strive to be seen taking part, office attendance will become ever more 'visible' with employees 'checking-in' so they are seen being seen. The paradox for senior managers is that for all the busyness, objects remain unmet, benefits unrealised, and staff unsatisfied with their role.

More than a millennia before Keynes, another luminary offered a solution to the problem of the busyness paradox. Marcus Aurelius identified the critical role that eliminating non-essential tasks played in living a good life:

Most of what we say and do is not essential. Eliminate it, you'll have more time and more tranquility. Ask yourself, is this necessary?

Enacting the wisdom of the stoics is easier said than done. If for no other reason than reporting to an authoritarian boss (read micro-manager) greatly limits the efficacy of timeless philosophy — or for that matter practical tips. Which is why working for a leader-manager is crucial, and one of the most important things, much more than the company or brand, to try and achieve when switching roles.

That depressive note aside, there are several processes that can be adopted to ensure a more deliberative approach to work.

Eliminating the In-between

Minimising Interruptions

Interruptions are arguably the most significant source of poor concentration and lost productivity. Perhaps you have heard the adage that it takes twenty minutes to return to a state of focus after an interruption. This elevates the practice of time boxing to pole position when it comes to tactics for improving the quality and efficiency of our time spent on work. The basics involve turning off email notifications and settings times of the day to think about emails. This is essential as too often our replies can be ill considered or completely forgotten. I have had roles in the past where I have had to read through my sent items to remind myself what I said or what I approved. Not a good situation for a manager to be in.

Time boxing can be expanded to include a range of activities beyond email and can create a structure schedule to reduce the ease with which non-essential tasks can sidetrack our day. Time boxing can, when deployed effectively, enable engagement with deep, focused work. Such intentionality is a vital building block to avoiding the pitfall of shallow, fragmented task delivery.

There is a 'gotcha' in the time boxing approach. Namely, thinking that a time box equals delivery of that work. I have seen this with people who meticulosity plan out their week in their calendar app of choice. Perhaps you have seen this with colleagues as diary snooping seems to have become ever more prevalent since Covid:

- 9 am — Review emails.

- 9:30 am — Daily Standup.

- 10 am — Watch training video.

- 10:30 am - 12 pm — Plan for quarterly business review.

- etc.

In my view this is not time boxing but micro-boxing which, like micro-management, is to be avoided. In a true time box approach, blocks should be longer than 30 mins and must involve deep work. Simply putting time to spend against all tasks is only doubling down on the busyness paradox as the employee will finish the week feeling exhausted. Look back on all the myriad tasks and meetings they have 'done', yet wonder why the top of mount deliverable is no nearer.

Prioritise the Priorities

If you haven't read Dr Stephen Covey's book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People it should be on your list. While a little bit too 'pop-intellectual' for my usual recommendations, it is nonetheless packed with actionable insights for the busy person who lacks the time to pull this thinking from its original sources. One such gem is the 'Eisenhower Matrix' — though it should be noted the President of that name never claimed the idea for his own, only cited the principle used by an unnamed college president:

I have two kinds of problems, the urgent and the important. The urgent are not important, and the important are never urgent.

Dwight D. Eisenhower

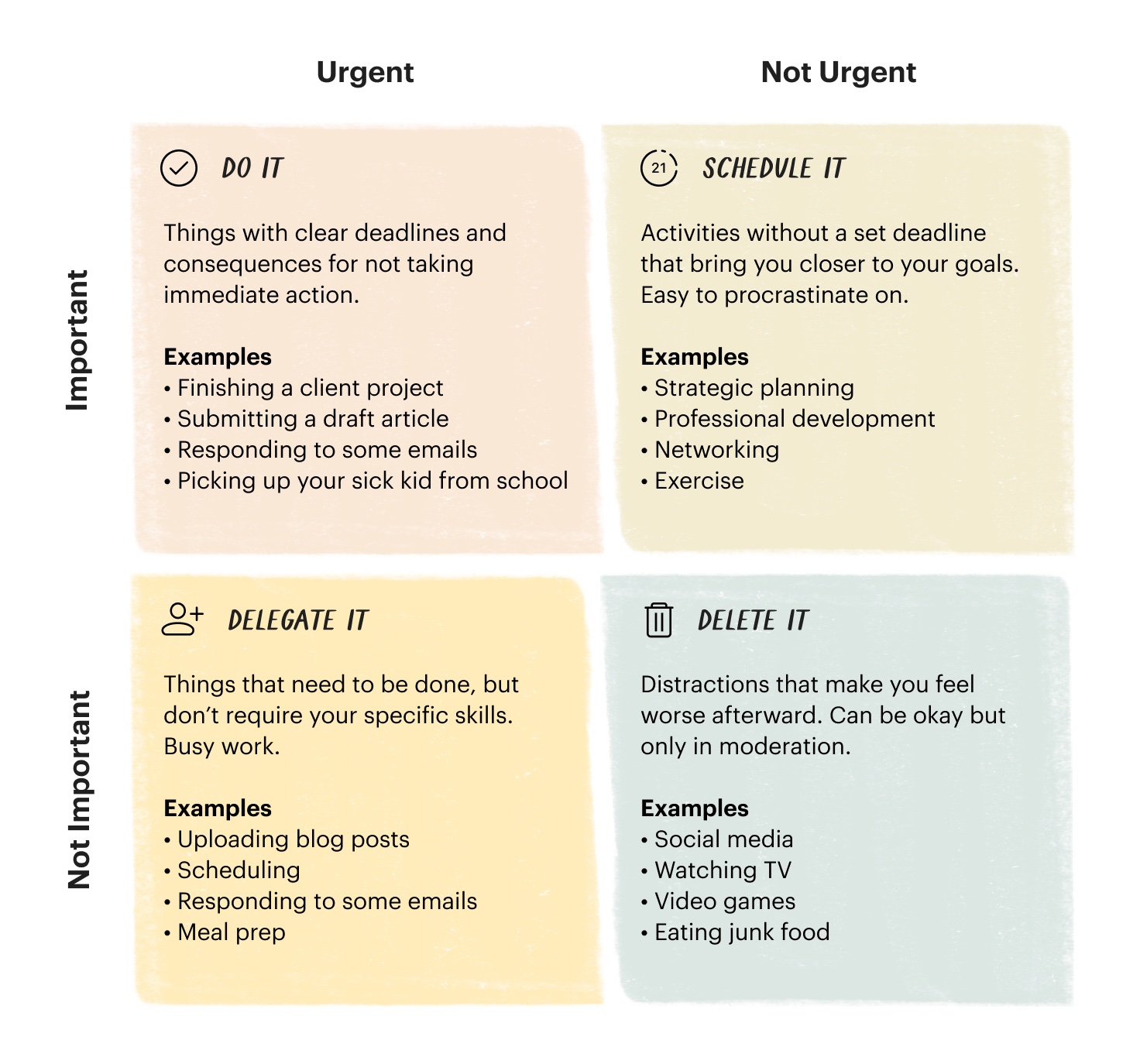

The college president being unnamed, Dwight D. was ascribed the naming rights. The process categorises tasks into quadrants based on their urgency and importance. By focusing on tasks that are important but not urgent, we can proactively address issues before they become crises.

Do what only You Can Do

This last principle is perhaps the hardest, particularly for those who are of the mindset "I wish I was a manager then I could just delegate work to other people". While people who are not managers may lack the positional authority to formally delegate, there is much any employee can do to accomplish the same result — and line managers, have no excuse.

In most roles, there are some things that only we can do. These are, even if our boss does not see it, the most important things we can do in a week. Why? Because of the self-evident reality that 'only we can do them'. An example of this might be to write a direct employee's performance review.

Given I am their line manager, given I have been working with them for the last year, and given no one else in the organisation either has the positional authority or knowledge of their performance to write the report, it is a report only I can write. To accomplish tasks which others could do, such as attending a 'for noting' meeting in which I am adding no value or reviewing non-essential documents which half a dozen other people are reviewing, is to substitute doing what is important for what is unimportant. Perhaps even something which is irrelevant, to take the fourth quadrant of the Eisenhower Matrix.

Assuming the work is not something that can be deleted I should delegate it. If I cannot delegate or am uncomfortable delegating, I should talk to my boss and gain official sanction for my thinking — which is to do what only I can do.

The Benefit of not Being Busy

In a world in which impressions invariably count for more than deliverables, not being busy has tremendous upside even if it initially feels uncomfortable.

When we concentrate on high-value tasks, we make more meaningful progress toward our goals, enhancing our productivity and job satisfaction. A study by McKinsey & Company found that employees who can spend more time on focused, meaningful work are 20-25% more productive than those who do not. And this statistic only climbs with roles which require critical thinking or when high performers are involved.

Creative thinking requires uninterrupted time and mental space. By reducing busywork and creating periods of focused, undistracted work, we can enhance our creativity and problem-solving abilities. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, in Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, explains that deep work and a state of flow are essential for creative achievements.

Mental health also sees a significant uptick when people can be productive rather than merely busy. By eliminating non-essential tasks and focusing on what truly matters, we can reduce stress, prevent burnout, and create more time for self-care and personal interests. A study published in the Journal of Occupational Health Psychology found that employees who prioritise essential tasks and maintain a healthy work-life balance experience lower levels of stress and higher overall well-being.

When we are not overwhelmed by busywork, we have more time to think critically and make informed decisions. Daniel Kahneman, in Thinking, Fast and Slow, emphasises the importance of deliberate, slow thinking in making sound decisions.

By adopting a more focused approach and eliminating non-essential tasks, we can improve our productivity, well-being, and overall quality of life. The wisdom of Marcus Aurelius, combined with modern productivity techniques, provides a valuable framework for achieving this. It is time to stop being busy and start adding real value to our lives and the lives of those around us.

Good night, and good luck.

Further Reading

Covey, SR (2020) The 7 habits of highly effective people: powerful lessons in personal change, Revised and updated edition, London: Simon & Schuster.

Csikszentmihalyi, M (1991) Flow: the psychology of optimal experience, New York: Harper Collins.

Hyatt, MS (2019) Free to focus: a total productivity system to achieve more by doing less, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Books.

Kahneman, D (2012) Thinking, fast and slow, London: Penguin Books.

Keynes, JM (1960) The general theory of employment interest and money, New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co.

Marcus Aurelius (2011) Meditations (R. Hard, Trans.), Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mark, G, Gudith, D, and Klocke, U (2008) The cost of interrupted work: more speed and stress., New York: ACM, , 107–110.

Newport, C (2016) Deep work: rules for focused success in a distracted world, New York: Grand Central Publishing.

Park, Y, Fritz, C, and Jex, SM (2011) Relationships Between Work-Home Segmentation and Psychological Detachment From Work: The Role of Communication Technology Use at Home. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16(4), 457–467.